What are the most common interventions for lonliness?

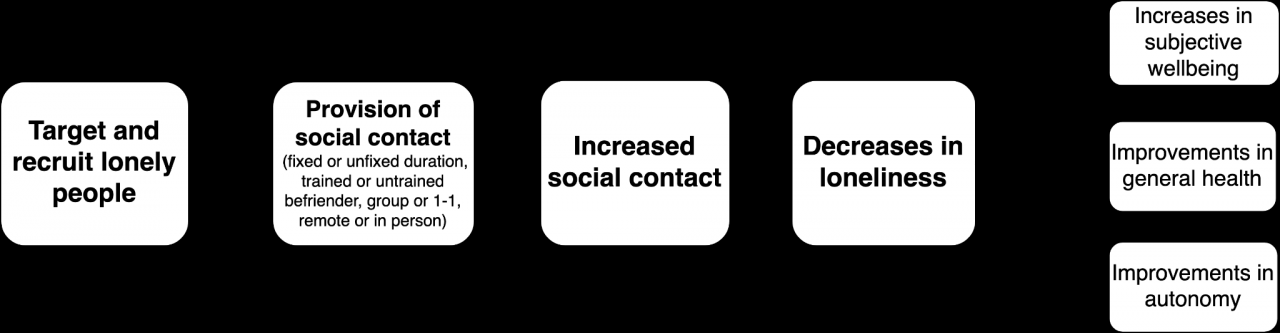

Befriending interventions

In these interventions, a ‘befriender’ visits or contacts a lonely person (e.g. in their home, a designated space, remotely). Befriending interventions are not typically structured and tend not to have formally defined goals either for each interaction or the overall course of the befriending sessions, but tend to prioritize the development of informal and natural contact. Befrienders may have received prior training (more often the case when providing care to patients with other conditions, e.g. dementia) or may be volunteers. Some interventions will try to match people by common interests or preferences.

According to one systematic review, compared to usual care (commonly no intervention) befriending has a small but significant effect on depressive symptoms in the short-term (standardized mean difference SMD=−0.27, 95% CI −0.48 to −0.06, nine studies) which likely decays over time, as evidenced by smaller effect sizes over the long term (SMD = −0.18, 95% CI −0.32 to −0.05, five studies; Mead et al, 2018). This review further pointed out that the current effective evidence for befriending interventions does not meet the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence’s depression guidelines for adoptions (SMD of 0.5 or more).

Befriending: A potential theory of change graph

Befriending interventions: some cost-efficiency data

- In the Netherlands, providing a befriending service to recently bereaved widows and widowers (n=110 intervention, vs usual care n=106) was associated with a cost per 1 QALY gained = €6,827, median ICUR of €4,123 where primary outcome was a general health related quality of life status (via the EQ-5D scale). These estimates only include direct costs. When indirect costs are included the ICUR is estimated at €11,239. Intervention participants had significant improvements but the intervention arm did not differ significantly from the control group in their changes in health-related quality of life over time. (Onrust et al., 2008)

- Importantly, Onrust and colleagues argue that befriending interventions for bereaved individuals will not produce large benefits for public mental health when targeted towards the entire population of all widowed individuals. They anticipate that widowed individuals will, over time, adapt and adjust and will not require a specific intervention to reach pre-bereavement levels of functioning. Moreover, they do not make frequent use of health care services related to bereavement. This is supported by additional research (Schut et al., 2001; Jordan & Neimeyer, 2011). A possible recommendation is to identify those who most benefit and need this type of intervention. It is also crucial to distinguish between general health or mental health needs and functioning versus needs for social opportunities and loneliness (directly measured).

- In the UK, carers for people with dementia (n=116 intervention, n=120 control) were offered a befriending service from trained lay workers and evaluated for quality of life and psychological well-being. There was no evidence for effectiveness nor cost-effectiveness. This intervention was linked to a cost per 1 QALY gained = £105,954. Further, there was no significant difference between intervention and control arms (RCT, Charlesworth et al, 2008).

- Bauer, Knapp and Perkins aimed to model the cost-effectiveness of the UK’s NHS running a befriending intervention, targeting lonely and socially isolated adults over 50, specifically by providing home visits for an hour per week for 12 weeks compared to usual care. Their model looked at reduction in depressive symptoms and reduction in use of health services as outcomes. This intervention was not cost saving over a 1-year time frame, as for every £85 invested (lower-end public cost of providing befriending) the NHS saved around £40 (Bauer, Knapp, & Perkins, 2011; section 2.15). The authors suggested that overall ‘befriending interventions are unlikely to achieve cost savings to the public purse, but they do improve an individual’s quality of life at a low cost.’ Further, when quality of life benefits associated with reduced depressive symptoms were included in a separate model, the authors suggested these interventions might be more cost-effective with an ICER of around £2,900.

- A friendship program involving older women (>55 years; mean age 63, sample size: 60 intervention, 55 control) with 12 weekly lessons on social topics (e.g. friendship, self-esteem; same intervention model as the ‘Friendship Enrichment Programme’) had significant positive effects on self-reported number of friends, self-esteem, life satisfaction, and loneliness for the intervention participants. Importantly, differences between the intervention group and control for loneliness was not significant (loneliness decreased by 4% in the intervention arm vs 3% for control, this wasn’t statistically different). It cost £77 per person at baseline and £120 per person including follow-up, and estimates a savings of £391 per person, and a gain of .035 QALY per person. (Optimity Matrix review for NICE, 2015; Martina & Stevens, 2006)

- This programme has also been probabilistically evaluated in Australia (Friendship Enrichment Programme, see Engel et al., 2021), where similarly modeling indicated the programme to be cost saving and, under some but not all probabilistic analyses, potentially cost-effective from a public health perspective (under A$50,000 per QALY gained).

Addressing barriers: How can befriending interventions be improved?

- Less demanding and lower cost training requirements for staff (see Richards & Sucklin 2009)

- Telephone or video-based systems (see Richards & Sucklin 2009)

- Evidence on peer befriending is limited but it could be a promising avenue to explore

- Hardly any evidence on befriending in LMICs and little on lonely young people

- Longer duration befriending interventions may be more effective and more wanted

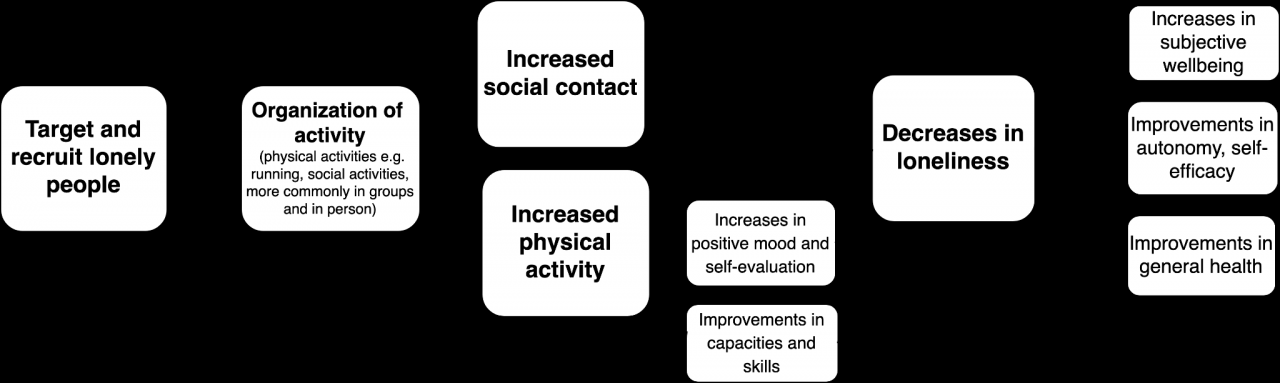

Participation in social and healthy lifestyle activities

In these interventions, an activity is provided that aims to bring people together. These can be purely social or otherwise target healthy lifestyles, provide training or education.

One qualitative review found 9 group interventions involving the provision of an educational service (Cattan et al. 2005). 5 of these interventions demonstrated a significant reduction in loneliness and 4 did not. Participants did not seem to be recruited on the basis of baseline loneliness (but rather e.g. recruited via media campaigns or all eligible patients on GP lists). A systematic review examining interventions for loneliness for adults living in long term-care facilities found support for the effectiveness that provide opportunities for social bonding and group activities, such as horticultural therapy and laughter therapy (Guan et al., 2019).

Participation in activities as a loneliness interventions: A potential theory of change graph.

Social & healthy lifestyle interventions: some cost-efficiency data

- ‘GoodGyms’ is an intergenerational intervention bringing together old and young runners. Here, 1 QALY gained = £8000, likely that there’s a return on every £1 invested of up to £4.56 (only considering at health and economic benefits; Ecorys UK)

- An arts-based intervention in the USA involving 30-weeks of chorale singing was narrowly cost saving, with a running cost of £86 per person and an estimated yield of health system savings of £92 per person. (Optimity Matrix review for NICE, 2015)

- An internet and computer training program (e.g. use of email, Internet) for older people was linked to costs of £564 per person and had an ICER of £15,962 per QALY gained. Importantly, this intervention did not have a statistically significant impact on participants’ loneliness and depression. (Optimity Matrix review for NICE, 2015)

Addressing barriers: How can social & healthy lifestyle interventions be improved?

- Group social interventions seem more effective than 1-1 interventions and so group interventions should be given priority consideration when feasible (Cattan and colleagues 2005)

- Targeting of those experiencing loneliness is not common and is a key problem

- There is evidence to suggest more specific targeting (e.g. care-givers, recently widowed people, physically inactive people etc.) and provision of appropriate, relevant services is associated with better outcomes (Cattan and colleagues 2005)

Signposting/ navigation services

These interventions generally do not provide a direct or frequent service but rather refer people to service or appropriate resources. Evidence is somewhat scarce and largely hails from observational studies.

Cattan and colleagues (2005) found 4 interventions that provided health assessments with information services. 3 large-scale RCTs were not effective in reducing loneliness and 1 study seemed promising in that a one-off home visit by a nurse to provide advice, referrals and written health information demonstrated a significant reduction in loneliness but this effect wore off soon after the visit.

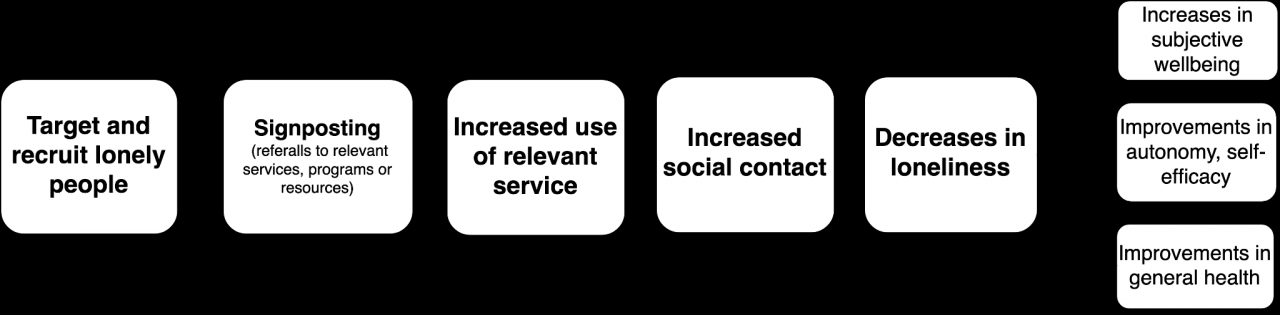

Signposting as a loneliness intervention : A potential theory of change graph.

Signposting interventions: some cost-efficiency data

- McDaid, Park, & Knapp, 2017 find a positive but small return on investment from a signposting to various activities: for every £1 invested, £1.26 returned (only looking at benefits to mental health) so could go up to £2-3 saved per pound invested.

- It seems most of these services don’t successfully target people experiencing more severe levels of loneliness

Addressing barriers: How can signposting interventions be improved?

- Better targeting is essential but given the existing evidence base it is unclear if that alone will make this stream of interventions effective.

- At present, it may be more appropriate to support interventions providing direct services.

Psychological interventions

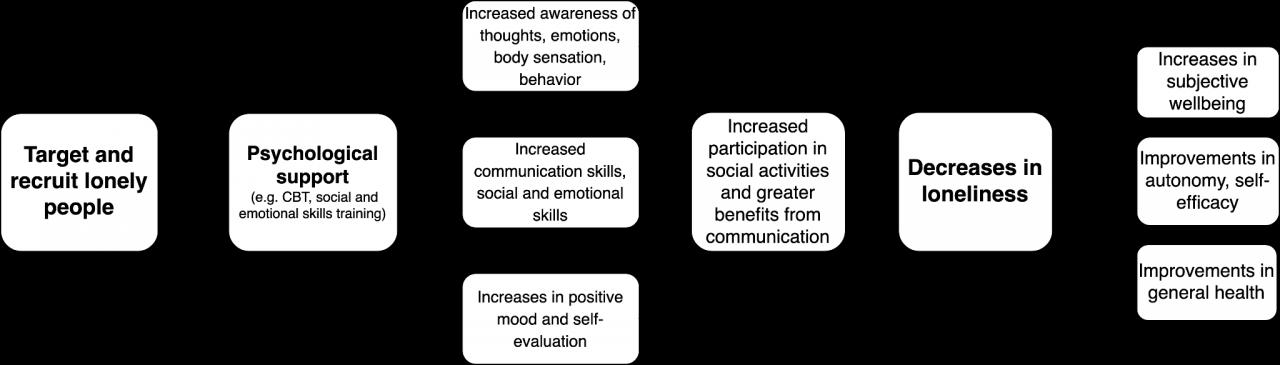

Psychological interventions, such as CBT or provision of social skills training, seem cautiously effective in reducing loneliness. While Hickin et al. (2021) find an overall medium effect size (g = 0.43) this is based on a relatively low (k = 28 studies but only n = 3039 for the meta-analysis) and very heterogeneous sample (e.g. all ages, with and without other health problems). Notably some of the included studies have no follow-up or only a short follow-up. The causal mechanism is unclear. I speculate that psychosocial therapy likely improves self regulation, mood and may help provide social skills for people who need them but equally, since these interventions are delivered in social contexts (in groups or 1-1 with therapist or trained practitioner) they also provide social contact which may (temporarily) reduce loneliness (rather than the psychological component of the intervention). It seems that provision of psychosocial therapies (which can be costly due to training and costing of time for clinicians) should be more carefully considered and a relevance profile for the targeted population should be established first. For instance, it appears inappropriate to offer psychological service to socially isolated people whose core need is social contact and who do not otherwise have problems with social skills or psychological problems.

Where might such services be most effective and warranted? One meta-analysis (Eccles & Qualter, 2021) examining loneliness alleviation in young people provides evidence for the effectiveness of a variety of interventions under this umbrella, including social skills training, social + emotional skills training, and psychological interventions (with no significant differences between intervention types, effect sizes varying around g=.262 to .350). This should still be taken with caution as most youth were recruited as they were considered to be at risk for e.g. health conditions, and were not targeted because of their reported loneliness. It is also unclear whether any reported levels of loneliness spoke to transient or chronic states. Future work should provide better targeting and measurement. Nevertheless, as adolescence is a particularly important period where social skills are still developing, these interventions might be particularly suited for this age group and may potentially become more cost-effective with better targeting. I note as well that included studies in this review involved young people living with physical health problems (e.g. HIV; cerebral palsy) but some of these interventions targeted young people or children with mental health or behavioral or developmental disorders, for instance autism, social anxiety disorder, behavioral disorders, and complex communication needs (e.g. as a result of physical disability). Outside of this age range, more careful consideration about social skills need and support are warranted to provide appropriate interventions, which likely include psychological interventions.

A ‘happiness’ intervention: cost-efficiency data

- In the Netherlands, a randomized single blind trial targeted people who experienced loneliness, health problems and reported low socioeconomic status (n=58 intervention, 50 control). The intervention “Happiness Route” provided home visits by a counselor who offered a happiness based approach in the intervention arm. The primary outcome was wellbeing but there were no significant improvements over time. The researchers estimated that expected costs per 1 QALY was €219,948 in the Happiness Route relative to control (Weiss et al., 2020).

Addressing barriers: How can psychological interventions be improved?

- More careful consideration of the needs of the population targeted (e.g. age, existing mental health problems or current communication skills).

- Considering attrition is relevant, particularly as there is some evidence to suggest that patients with depression are most likely to drop out of CBT (Fernandez et al., 2015). Further support may be warranted for some, according to risk profile.

- Providing CBT or other clinical therapies can be costly (e.g. therapist training, time) so this should be carefully offered. Alternatives like trained volunteers should be considered, as these seem promising in other contexts.

Like Our Story ? Donate to Support Us, Click Here

You want to share a story with us? Do you want to advertise with us? Do you need publicity/live coverage for product, service, or event? Contact us on WhatsApp +16477721660 or email Adebaconnector@gmail.com