Shallow investigation: Loneliness

This is a shallow report examining loneliness.

In a nutshell

|

Key uncertainties

The current interventional evidence base is predominantly cross-sectional or short in duration, marked by relatively small and not globally representative samples, so it is hard to make strong causal claims as well as claims with high certainty for generalizability. There are few longitudinal interventions, so little is known about the long-term impacts and potential sustainability of such projects.

Some of the promising interventions to tackle loneliness require significant involvement in terms of time and service provision, and so may be difficult to scale. Compounding this difficulty, many of the most socially isolated people live rurally or in poorly connected areas and so reaching them may be challenging.

A surprising key target many current anti-loneliness interventions miss is actually recruiting participants who are lonely. I anticipate this is an essential part to understanding the real cost-effectiveness of available interventions. Beyond this, provision of a relevant intervention type for the relevant group as well as provision for a sufficient length of time are also warranted. |

Importance

Problem Overview

| Question | Answer |

| Definition of the problem | Loneliness is commonly defined as a discrepancy between a person’s desired and actual social relationships or opportunities for social contact. This can be a subjective (perceived) or objective discrepancy (social isolation). Loneliness is a risk factor for a variety of general and mental health conditions, mortality, loss of productivity, and poor self-esteem. |

| Burden of the problem | Health burden:

Productivity burden:

Wellbeing burden:

I note the difficulty in providing global burden estimates as almost all data comes from high income settings and we know little about the distribution of loneliness and its impacts in LMICs, where healthcare costs also tend to be markedly different. |

| Who is affected at what point in their life | Gender of people affected: Both men and women.

Age of people affected: Tends to be more common in older age (though possible at any age). Situation in which they are affected: Experiencing social isolation, living alone, having fewer opportunities for social contact, becoming widowed, having poor health and chronic health problems, especially in older age. |

Introduction to the problem

Loneliness is commonly defined as a discrepancy between a person’s desired and actual social relationships or opportunities for social contact (Russell, Peplau, & Cutrona, 1980). This can be a subjective discrepancy (perceived loneliness) or objective discrepancy (social isolation). Loneliness should be distinguished from merely being on your own and related concepts such as solitude, defined as a state of internal focus (Weinstein, Hansen, Nguyen, 2022).

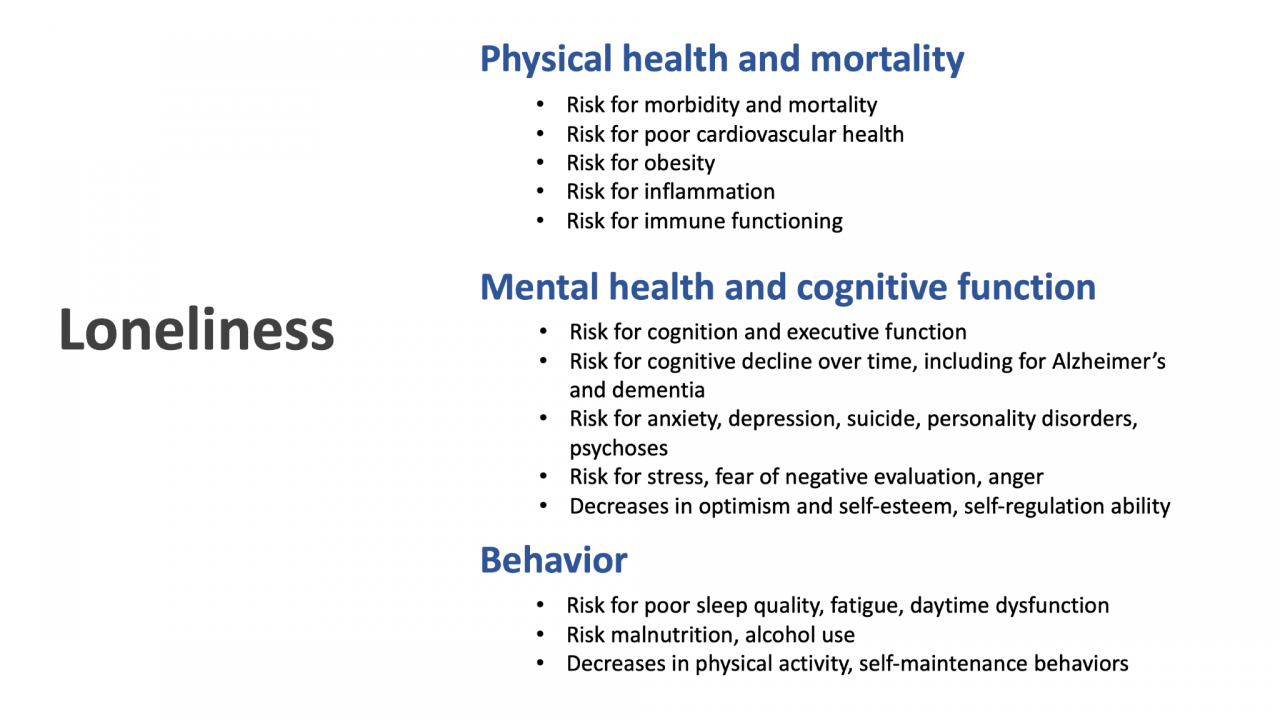

Loneliness is a risk factor for a variety of general and mental health conditions, mortality, loss of productivity, and poor self-esteem among others. The mechanisms and quality of evidence tying loneliness and different conditions are varied ranging from very strong and likely causal (e.g. impacts on depression) to still poorly understood and mostly correlational (e.g malnutrition, inflammation).

There is some discussion about whether or not loneliness has been increasing. One recent meta-analysis (k=345) suggests this might be the case; for emerging adults (n=124,855) over the last 43 years, loneliness has been increasingly with each calendar year (b=0.224, 95%CI [0.138, 0.309]), corresponding to 0.56 standard deviations on the UCLA loneliness scale (Buecker et al., 2021).

Quick outline of loneliness as a multi-domain risk factor based on a literature review.

What parts or aspects of loneliness carry the greatest risk or are most associated with the heaviest burden?

Severity

One meta-analysis (k=70) examined the impacts of social isolation (defined as a pervasive lack of social contact or communication, participation in social activities), loneliness (defined as experiencing feels of isolation, disconnectedness, and not belonging) and living alone (measured as a binary yes/no item) on mortality. After adjusting for potential confounds, the weighted average effects size were: social isolation odds ratio (OR = 1.29, loneliness OR = 1.26, and living alone OR = 1.32), corresponding to an average of 29%, 26%, and 32% increased likelihood of mortality (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2015). While these numbers are fairly similar, they would still coarsely suggest that greater levels of isolation carry a greater burden for mortality. Another review focusing on the economic toll of loneliness (k=12) similarly found that social isolation was associated with higher economic costs than loneliness (Mihalopoulos et al., 2019). Social isolation seems well established as a risk factor for all cause mortality based on a recent meta-analysis with data from 1.3 million individuals (hazard ratio 1.33 (95% confidence interval; 1.26-1.41, heterogeneity: Chi² = 112.51, P < 0.00001, I² = 76% ) Naito et al., 2023).

Frequency

One longitudinal 50-year study (n=7,638) suggested both situational and chronic loneliness were associated with higher risks for all cause mortality, with chronically lonely individuals (HR = 1.83; 95% CI: 1.71–1.87) exposed at slightly greater risk for mortality than those who were only situationally lonely (HR = 1.56; 95% CI: 1.52–1.62; Shiovitz-Ezra & Ayalon, 2009).

In another study, involving a 4 year follow-up (n=2,390), for both transiently lonely and chronically lonely people there were negative significant general health impacts (e.g. vision, mobility, self-care; Martín-María et al., 2019). Here, too, chronically lonely people had worse health than transiently lonely individuals (transient: β = −0.063 and chronic: β = −0.075, p < 0.001). Another study (n=2,995, 6 year follow-up) supports this pattern, where both transiently and chronically lonely people reported worse cognitive function, with the chronic loneliness being associated to more pronounced negative cognitive impacts (transient: β = −0.389, t = −2.191, df = 2994, p = 0.029; chronic: β = −0.640, t = −2.109, df = 2994, p = 0.035).

In summary, the evidence suggests that experiencing loneliness, regardless of severity or frequency, likely will bear negative implications for health, although the greatest burden of health problems will be experienced by those reporting chronic loneliness and the most severe levels of loneliness or isolation.

Like Our Story ? Donate to Support Us, Click Here

You want to share a story with us? Do you want to advertise with us? Do you need publicity/live coverage for product, service, or event? Contact us on WhatsApp +16477721660 or email Adebaconnector@gmail.com