By Phillip van Niekerk

18 Jan 2023

Every election cycle, there is the hope that something new will break through, a miracle. The next month’s presidential elections are no different.

The journalist Howard French, writing in the UK’s Guardian newspaper, makes the point that the urban portion of West Africa, of which Nigeria is a major part, will shape the coming century.

“By 2100,” he writes, “the Lagos-Abidjan stretch is projected to be the largest zone of continuous, dense habitation on Earth, with something in the order of half a billion people.”

Nigeria has that X factor — its dynamism, music, movies, literature, innovative, tech-savvy youth culture and the achievements of Nigerians on the global stage provide a sharp contrast to the curse of its poor leadership.

In 1983, the great Nigerian writer Chinua Achebe published a slim volume titled The Trouble with Nigeria, in which he blamed the country’s leadership for the endemic problems of tribalism, social injustice, mediocrity and corruption. It says something that this book is still high on the list for any journalist or student visiting the country for the first time.

Speak to any Nigerian and the lament is always couched as the failure of the promise. Every election cycle, there is the hope that something new will break through, like a miracle that will transform a chaotic underachieving nation into the giant of Africa that it should be.

The focus of next month’s presidential elections has been on Peter Obi, the third-party candidate who has run a ballsy, upbeat campaign that aims to break the mould of the country’s two-party system dominated by big men and big money.

London rolled out the red carpet for Obi this week: Chatham House, the London Stock Exchange and the Archbishop of Canterbury all welcomed him as a breath of fresh air.

Obi has been embraced on social media and hailed by many in the international media as a different kind of Nigerian politician. The Economist was charmed by the fact that he carries his own suitcase when he travels.

One supporter in Bayelsa state summed it up: “Obi’s biggest attraction to many is the lack of skeletons in his closet. They have nothing on this guy. It seems almost too good to be true. A Nigerian politician who is actually clean? I have never seen anything like it before in my life.”

But the next president of Nigeria will not be elected on TikTok or by the editorial board of The New York Times.

It’s the demographics, stupid

Nigeria’s electorate has a long history of voting along regional, religious and ethnic lines, and there is no reason that should change now. In the 2019 election, General Muhammadu Buhari won in a landslide with 55% of the vote — 15.1 million votes — against Atiku Abubakar of the People’s Democratic Party, who received 41% (11.2 million). Very few of Buhari’s supporters in the North are likely to migrate to Obi, an Igbo Christian from the South East.

Of the six regions, Obi stands to do well in the South East and the oil-rich South South, as well as in the Christian majority states in the Middle Belt. But he lacks even a rudimentary electoral infrastructure in the vote-rich North where his rallies have been poorly attended.

Unlike Obi’s Labour Party, the ruling All Progressives Congress (APC) has national reach and has fielded candidates in almost all constituencies.

Atiku, the perennial candidate, who is standing for the Peoples Democratic Party again, will lose votes in the South to Obi, who was his running mate last time, but as the only major northerner in the race will hope to make up for them up in the North.

In the last election, Buhari crushed Atiku in the North West. In just two states, Kano and Katsina, Buhari got a million more votes than Atiku’s entire haul in the South East, his strongest region.

The North West, which holds the key to the election, looks set to remain ruling party territory irrespective of disappointment with Buhari. And if there is to be an anti-ruling party vote, it will be split between Atiku and Rabiu Kwankwaso, the former governor of Kano, who is running on a fourth-party ticket.

The Godfather

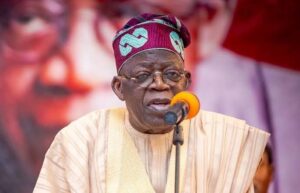

Despite Obi’s recent celebrity, the most interesting — and underestimated — candidate is Bola Tinubu, who is representing the ruling party.

Many international journalists have dismissed him as part of the corrupt old order that Nigeria needs to move beyond. And indeed he is a puzzling potential president.

He doesn’t show up for debates with his opponents, and he is not noted for being a good speaker. He has the demeanour of a backroom wheeler-dealer, and indeed is the model of a political godfather. There are rumours about his health, though people who have been with him say he is perfectly cogent. Tinubu is also exceedingly wealthy, with all the accompanying question marks about where he got it all from.

As the candidate of a party that has ruled Nigeria for eight lacklustre years, Tinubu should by rights be facing a tough electoral challenge.

But he is a canny politician. In 2014, he created the APC as an alliance between the six states in the South West and North political interests to forge an unbeatable electoral combination. He helped Buhari, who was thrice defeated as a presidential candidate, to rehabilitate his political career and agreed to let him head the APC ticket because he brought with him 10 million supporters in the north.

Once he took power, Buhari marginalised Tinubu, and ran the country on a much narrower agenda. Last year, Buhari tried to prevent Tinubu from getting the APC nomination but Tinubu managed to detach 11 younger, reformist governors from Buhari, a rare political achievement.

Now, the president, who retains a loyal following in the vote-rich North West, has bestowed his blessing on Tinubu and will be campaigning for him.

Tinubu’s running mate is Senator Kole Shettima, the former Governor of Borno state, who is also Muslim. This Muslim-Muslim ticket was once regarded as a disadvantage for Tinubu in a country that is equally divided between Christians and Muslims. But it works in his favour in the geographical belts that will decide the election.

The best hope for Obi and Atiku is if they can force Tinubu into a second-round run-off and, by combining forces, defeat him in the second round. This is possible but not certain.

Perhaps alarmingly, given Nigeria’s sometimes chaotic electoral history, huge expectations have been created and some commentators have implied that the only way Tinubu can beat Obi is by cheating, creating a Trumpian-style Hobson’s choice: “Either he wins or it’s rigged.” That is as dangerous in Nigeria as it was in the US.

Going downhill fast

Whoever gets elected will have to contend with a country in deep crisis after eight years of Buhari, who came to power democratically in 2015 vowing to do three things — tackle corruption, combat insecurity, especially the Boko Haram insurgency, and fix the economy — but achieved none of them.

The last eight years have seen stagnation and decline. Some of the causes — such as the fall in the oil price and the Covid pandemic — could not be helped. But Buhari appeared more devoted to the entrenchment of a powerful northern clique around him than actually governing a diverse country of 218 million people.

Read in Daily Maverick: “Life after Muhammadu Buhari – political rhetoric, governance and the media in Nigeria”

Between the end of military rule in 1999 and the election of Buhari in 2015, Nigeria’s GDP growth averaged more than 7% per annum. Since Buhari was elected in 2015, growth has averaged little above 1% per year. With the population growing at 2.5% every year, Nigeria has slid downhill during the last eight years.

The crash in oil production, which has halved over the last few years, has forced Nigeria to borrow to finance its budget: more than 60% of the Nigerian budget is now funded through debt. According to Finance Minister Zainab Ahmed, the cost of servicing the debt has surpassed revenue.

The number of Nigerians in absolute poverty has soared, while talented members of the middle class are moving abroad, a brain drain described by the Yoruba word “japa”, which means “to run away from a bad situation”. Nigerians are snapped up in the UK, Canada and the US, where they are among the most successful immigrant communities.

High unemployment and lack of opportunity have left poorer Nigerian youths jobless and stranded in secondary cities where selling cooldrinks or their bodies on the street is sometimes the only option for survival. Hundreds risk their lives to cross the Sahara Desert and to get across the Mediterranean in rickety boats.

Those who stay are among the recruits for the bandits and jihadis who are at the forefront of the domestic insecurity that includes an insurgency that is spreading in geographical reach; clashes between Fulani herders and farmers; oil pipeline pirates in the Niger Delta; separatists in the South East; and kidnapping and ransom activity throughout the country.

Much of the violence has been stomach-churning: the kidnapping and murder of children; hijacking of trains; hostage taking; and the bombing of churches.

Not just a pipe dream

The challenge of the election is whether anyone can turn Nigeria around.

When it comes to policy, there is little daylight or ideological difference between the candidates. All say they favour a pro-business free market policy that would require a more efficient and less bloated federal government.

On the hot-button issues, they agree on ending the fuel subsidy, cancelling the two-tier exchange control system, cutting government spending and negotiating debt relief. They all want to crack down on corruption and ramp up security.

Any of the three major candidates will offer Nigeria something better than what it has had during the last eight years.

As governor of Lagos (1999 to 2007), Tinubu was an effective leader and instituted a number of reforms and projects that turned the city-state into one of the fastest-growing economies in Africa.

As vice-president from 1999 to 2007 under Olusegun Obasanjo, Atiku managed a brilliant team of reformers and technocrats who masterminded Nigeria’s extraordinary rise in the first 15 years of the 21st century to become the largest economy in Africa. (It has fallen to third place since 2015.)

Obi was a competent governor of Anambra between 2007 and 2014, helping drive a region that has seen remarkable development even as it has been neglected by the federal government.

Nigeria has found itself in the doldrums before. When 16 years of military rule ended in 1999, the country was economically bankrupt and the government barely functioned. But a competent, reformist government under Obasanjo released a pent-up dynamism that lasted for a decade and a half.

The overriding issue in Nigeria, one that it has grappled with since its independence from Britain in 1960, is to bring all the different parts of such a diverse country into some form of harmony, to forge a united country.

For Nigeria writ large, the security and political issues converge. It is about balancing the regional, religious and ethnic interests, and neutralising those who believe that violence is the best way to extract a greater share of the national cake.

Traditionally, this has been done by carving up the oil revenue among the elites, leaving the masses to find their own way. The Nigerian petrostate was by its very nature based on patronage and rent-seeking. This is increasingly less of an option.

A united and prosperous Nigeria is not a pipe dream. But it’s going to take work, modernisation, big ideas and some really tough decisions.

Like Our Story ? Donate to Support Us, Click Here

You want to share a story with us? Do you want to advertise with us? Do you need publicity/live coverage for product, service, or event? Contact us on WhatsApp +16477721660 or email Adebaconnector@gmail.com