Ok, first of all, to be clear, ancient Egyptians and modern Egyptians are not the same people strictly speaking. The ancient Egyptians are all dead; whereas modern Egyptians are living people, most of whom are probably remotely descended from the ancient Egyptians.

Furthermore, the ancient Egyptians did not call the continent of Africa “Kemet.” The ancient Egyptians do not seem to have had a name for the entire African continent. The Egyptians did, however, refer specifically to the land around the Nile River in which they themselves lived using the name “Kmt,” which is written in hieroglyphics as follows:

The ancient Egyptians did not normally write using vowels, so we don’t know what the vowel sounds in the word “Kmt” were. Modern scholars have inserted the letter ⟨e⟩ between the consonants in order to make the name pronounceable in English, but we really don’t know exactly what the vowel sounds were. In modern Coptic Egyptian, the name for Egypt is ⲭⲏⲙⲓ (Khēmi), which comes directly from Ancient Egyptian “Kmt.”

The name “Kmt” literally means “the black land.” This name refers to the extremely fertile black soil that is found in the areas around the Nile River. The ancient Egyptians frequently contrasted the fertile “black” soil of the lands where they lived with the barren “red” sands of the desert. They called the desert “dšrt,” which means “the red land.”

Contrary to what some people have asserted, the name “Kmt” is almost certainly describing the land itself, not the color of the skin of the people who lived there. The ancient Egyptians did not define themselves in terms of their skin color and, in fact, there was a great deal of variation in skin tone in ancient Egypt, just as there is in Egypt today.

ABOVE: Photograph of Egyptian soil. The soil is extremely dark because it is extremely fertile.

Replys

Actually we do know Roughly what it sounded like:

Coptic renders the word as Kēme; the long e comes from an original u (long/stressed)The second e comes from what was once -at (often -ah—like in Classical Arabic)

So back in the day, they called their country kumat (roughly pronounced as “KOO-mutt”, later Kuma, then Kēme. EDIT:: this guy explains it more

Ibrahim G Zalloum, My only issue with this video is with the use of the term ‘land’. The glyph for land is not included as a determinative, anywhere within the term Km.t. So, Km.t does not mean the Black land. The ideogram/glyph symbolizes a Village/Metropolis/Town-Site/Inhabited Region/City/Nation.

So, Km.t is a collective noun and it literally means ‘the Blacks’ and symbolizes the Black people of the Black Nation/the Black Country. As to the determinative, we must deal with the first glyph (letter) in the word Km.t. That glyph is a charred piece of wood, representing the letter K, and is the strongest glyph for Black in MDW NTR language.

The collective noun Km.t when it was written, used these glyphs to write it.

(1) a charred piece of wood, which symbolized the strongest term for Black in MDW NTR (Hieroglyphs), representing the letter K.

(2) an Owl, representing the letter M.

(3) a loaf of bread, representing the letter T.

(4) And finally, the glyph (ideogram) of a Village, Inhabited Town-Site, inhabited Region, City, to represent the Black Nation–. (Km.t).

When writing the collective noun Kmtyw you add the glyph of a seated man and woman with 3 determinative strikes, underneath, representing the collective group of Black people, representing the Black people of the Black Nation. It means the Black Nation.

As we can clearly see, the collective noun Km.t does not mean the Black land as the glyph for land is not included anywhere within the word Km.t at all.

And anyone claiming Km.t means ‘Riparian Land’ i.e. ‘the Fertile farmland’, is either lying or he or she doesn’t know what they are talking about and is absolutely incorrect. The collective noun Km.t does not mean ‘Riparian Land’ (‘the Fertile farmland near a river’) because neither the glyph for ‘land’ and/nor the glyph ‘river’ is included nor written anywhere within the collective noun, Km.t at all. There are no water-determinant glyphs or land-determinant glyphs written or contained within the written collective noun, Km.t anywhere. Those making this false, pseudo narrative are either ignorant or are intentionally acting as if the Kmytw (Egyptians) did not have a separate glyph for ‘land’ and/or a separate glyph for ‘river’ within their written language. And they are trying to insinuate that the ancient Kmtyw didn’t know how to include either of these glyphs when writing the collective noun Km.t.

The fact that the language of the ancient Kmtyw possessed a glyph for ‘land’, possessed a glyph for a ‘river’, and possessed a glyph for ‘Village/Town-Site/Inhabited Region/City/Metropolis/Nation/Country’ within their language and did not use either the glyph for ‘land’ or use the glyph for a ‘river’, as a determinative, whenever they wrote the collective noun, Km.t. proves it does not mean what these pseudos claim it means. This proves these pseudos’ entire assertion on the collective noun Km.t to be incorrect and completely false. The collective noun Km.t and its meaning, linguistically does not support such an incorrect conclusion that Km.t means ‘the Black land’ or ‘Riparian land’, or represents a waterway or a canal, for that matter, despite what some pseudos have incorrectly argued here. That is a completely incorrect conclusion and is not based on the ideogram

for a Village-Town-Site/inhabited Region/City/Metropolis/Nation/Country that is included within the collective noun, Km.t.

And such an incorrect pseudo idea is not supported by any bonafide Linguists or Linguistic ‘Peer-Reveiwed’ research at all.

So, there are no mistranslations nor anything else incorrect contained in anything I’ve presented here.

Townsite-city-region (hieroglyph)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Townsite-city-region_(hieroglyph)

Here are the glyphs for land and a river

Here is the symbol that represents land in their language. The word for land in MDW (Hieroglyphs), is Ta, as in Ta-Merri (Land of the beloved), Ta-Wii (The United Two Lands), Ta-Seti (Land of the Bow), and Ta-Nehisi (Land of the Ancients), Ta-Neter (The Land of the Creator).

As you can see, the symbol for the land is not contained, included, or written anywhere within the term Km.t at all.

Here is the symbol of United Two lands

Ta-Wii (The United Two Lands).

Here is the glyph that represents land in their language. It is Ta, as in Ta-Merri (Land of the beloved), Ta-Wii (The United Two Lands), Ta-Seti (Land of the Bow), and Ta-Nehisi (Land of the Ancients), Ta-Neter (The Land of the Creator). As you can see, the glyph/determinative for the land is not contained or written anywhere within the collective noun, Km.t at all.

Here is the glyph representing land. Ta=Land or Land of

Here is the glyph for land

Here is the glyph for a river

And, clearly, the glyph for a River is not included or written within the collective noun Km.t. Therefore, the collective noun Km.t cannot mean ‘Riparian land’ (Things that exist along the River/Wetlands). As you can see, the glyph/determinative for a river is not contained or written anywhere within the collective noun, Km.t at all.

https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/riparian

Here is a quote by E.A. Wallis Budge, (7/27/1857-11/23/1934)

on ancient Kmtyw (Egyptian) and their indigenous Nile Valley Afrikan language, proving it is not a Semitic language

“It is still impossible to me to believe that Egyptian is a Semitic language fundamentally. There is, it is true, much in the Pyramid Texts that recalls points and details of Semitic Grammar, but after deducting all triliteral roots, there still remains a very large number of words that are not Semitic, and were never invented by a Semitic people. These words are monosyllabic, and were invented by one of the oldest African peoples in the Valley of the Nile, of whose written language we have any remains. These are words used to express fundamental relationships and feelings and beliefs which are peculiarly African and are foreign in every particular to Semitic peoples. The primitive home of the people who invented these words lay far south of Egypt, and all that we know of Predynastic Egyptians suggests that it was the neighborhood of the Great Lakes, probably to the east of them.”—An Egyptian Hieroglyphic Dictionary: In Two Volumes”, Vol.1, Introduction, page lxviii, by E.A. Wallis Budge

“The ancient Egyptians were Africans and they spoke an African language…”—”An Egyptian Hieroglyphic Dictionary: In Two Volumes, Vol.1″, Introduction, page lxix, by E.A. Wallis Budge

—”An Egyptian Hieroglyphic Dictionary In Two Volumes”, Vol.1, page Cxxv, by E.A. Wallis Budge

The UNESCO Symposium was held in Cairo, Egypt between January 28, 1974, and February 3, 1974

“General History of Africa: Ancient Civilizations of Africa”, Volume #2, pp 27–29, Prepared by UNESCO, Editor, G. Moktar

‘The Egyptians as they saw themselves’

“The Egyptians had only one term to designate themselves

=kmt=the negroes (literally). This is the strongest term existing in the Pharaonic tongue to indicate blackness. This word is the etymological origin of the well-known root kamit, which proliferated in modern anthropological literature. The Biblical root kam is probably derived from it and it has, therefore, been necessary to distort the facts to enable this root today to mean ‘white’ in Egyptological terms whereas, in the Pharaonic mother tongue which gave it birth, it meant ‘black’. It is a remarkable circumstance that the Ancient Egyptians should never have had the idea of applying these qualifications to the Nubians and other populations of Africa to distinguish them from themselves. The Egyptians used the expression nahas to designate the Nubians; and ‘nahas’ is the name of a people, with no colour connotation in Egyptian. It is a deliberate mistranslation to render it as ‘negro’ as is done in almost all present-day publications.”

See also pp 28-30 of “General History of Africa: Ancient Civilizations of Africa ”, Volume #2, prepared by UNESCO, Editor, G. Moktar

“General History of Africa: Ancient Civilizations of Africa:Ancient Civilizations of Africa”, Volume #2, pp 31&32, prepared by UNESCO, Editor, G. Moktar

“In regard to linguistics, it is stated in the report that ‘this item, in contrast to those previously discussed, revealed a large measure of agreement among the participants. The online report by Professor Diop and the report by Professor Obenga were regarded very constructive. Similarly, the symposium rejected the idea that Pharaonic Egyptian was a Semitic language.

Turning to wider issues, Professor Sauneron drew attention to the interest of the method suggested by Professor Obenga following Professor Diop. Egyptian remained a stable language for a period of at least 4,500 years. Egypt was situated at the point of convergence of outside influence and it was to be expected that borrowings had been made from foreign languages; but the Semitic roots numbered only a few hundred as compared with a total of several thousand words. The Egyptian language could not be isolated from its African context and its origin could not be fully explained in terms of Semitic; it was thus quite normal to expect to find related languages in Africa. The genetic, that is non-accidental relationship between Egyptian and African languages was recognized…”

“The Peopling of Ancient Egypt and the Deciphering of the Meroitic Script”, by Cheikh Anta Diop, Jean Leclant, Theophile Obenga, Jean Vercoutter, page 89

The Final Report of the Symposium on ‘The Peopling of Ancient Egypt and the Deciphering of the Meroitic Script’, called the “Cairo Colloquium” – UNESCO, 1974 (the only major colloquium till date about Egyptology, gathering international Egyptologists) states:

“In so far as very ancient times were concerned -those earlier than what the French still called the ‘Neolithic’ period – participants agreed that it was very difficult to find satisfactory answers. Professor Debono noted the considerable similarity between pebble cultures in the different regions where they had been discovered (Kenya, Ethiopia, Uganda, Egypt). The same was true of the Acheulean period, during which biface core tools were similar in a number of regions of Africa. (…) It was probable that at the same time [Paleolithic] there was a small-scale admixture of other races, rapidly absorbed by the native population.”

“Generally speaking, participants considered that the ‘large-scale’ migrations theory was no longer tenable as an explanation of the peopling of the Nile Valley, at least up to the Hyksos period, when linguistic exchanges with the Near East began to take place (Holthoer) (…) At all events, it was generally agreed that Egypt had absorbed these migrants of various ethnic origins. It followed that the participants in the symposium implicitly recognized that the substratum of the Nile Valley population remained generally stable and was affected only to a limited extent by migration during three millennia”.

“The Peopling of Ancient Egypt and the Deciphering of the Meroitic Script”, by Cheikh Anta Diop, Jean Leclant, Theophile Obenga, Jean Vercoutter, page 100-101

“In response to Professor Diop’s statement that Egyptian was not a Semitic language, Professor Abdalla observed that opposite opinion had often been expressed. A grammatical and Semantic debate took place between Diop on the radical which reads KMT, derives from KM ‘black’ and considered to be a collective noun meaning ‘The blacks’, i.e. ‘Negroes’ and Professor Abdelgadir M. Abdallah who adopts the accepted reading of it as KMTYW and translation with ‘Egyptians’, the plural of KMTY ‘Egyptian’, the nisba-form from KMT ‘black land, i.e. Egypt’. The latter reading was affirmed by Professor Sauneron.

Professor Abu Bakr asked how frequently the form KEMTI occurred, Professor Obenga emphasized that the Egyptians did not apply the name Egypt to their country during Pharaonic times.”

“The Peopling of Ancient Egypt and the Deciphering of the Meroitic Script”, by Cheikh Anta Diop, Jean Leclant, Theophile Obenga, Jean Vercoutter, page 102

General conclusions

“Although the preparatory working paper (see Appendix 3, p. 135) sent out by UNESCO gave particulars of what was desired, not all participants had prepared communications comparable with the painstakingly researched contributions of Professors Cheikh Anta Diop and Theophile Obenga. There was, consequently, a real lack of balance in the discussions.”

Here is what Obenga wrote in his book entitled,“African Philosophy: The Pharaonic Period 2780–330 B.C.”, pp20–21, published in 2004 by Dr. Theophile Obenga

“Ancient Egyptian Language and Writing”

“Language”

“The language of ancient Egypt, in both its pharaonic and Coptic variants, is not an Indo-European language such as Hittite or Greek. Nor is it a Semitic language such as Akkadian, Hebrew, or Arabic. Neither is it a Berber language, such as Siwa Berber, or Rif Berber.

This much is unequivocally clear: no scholar, applying methods of historical linguistics based on comparative and inductive techniques, has ever reconstituted a primitive, pre-dialectal ancestral language common to ancient Egyptian and the Indo-European languages. Similarly, no scholar using those valid methods has been able to establish common linguistic roots for ancient Egyptian and the Semitic and Berber languages. To put the issue in even plainer terms, there is no genetic linguistic kinship linking the language of ancient Egypt to the Semitic and Berber languages, or to the Indo-European languages, in any strictly scientific sense.

By contrast, the Egyptian language does have genetic kinship affinities with other continental Black African languages, ancient and modern. That is why the 1974 UNESCO International Colloquium, organized in Cairo, explicitly urged experts in comparative linguistics ‘to establish all possible correlations between African languages and ancient Egyptian language’, given the impossibility of identifying genetic links between the language of ancient Egypt, on the one hand, and the Semitic and Berber languages, on the other.

The meaning of that resolution was a recognition that the old attempts to establish so-called Hamito-Semitic or Afro-Asiatic linkages, dear to many a mildewed school of thought are based on simple uninformed speculation, quite empty of intellectual substance.”

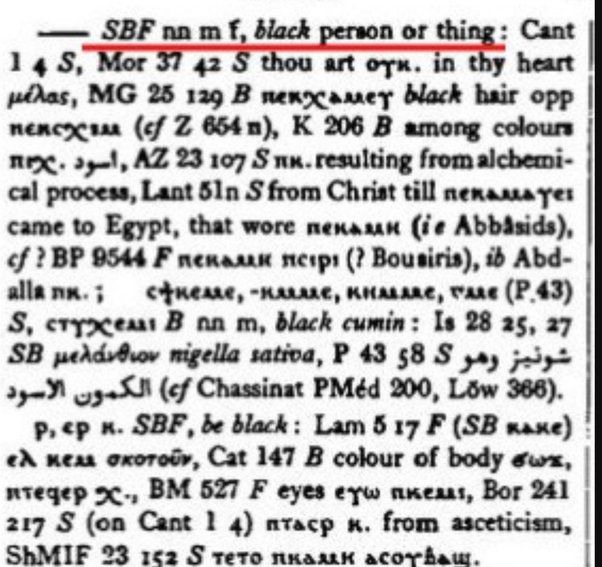

This screenshot below comes from the book entitled, “A Coptic Dictionary” by W. E. Crum pp 109–110

So, even in Coptic, a living remnant of the old language of the Kmtyw (Egyptians), Kemiu means ‘The Blacks’. This is in all 3 dialects of Coptic. Those 3 dialects are Sahidic, Bohairic, and Fayyumic.

References

1. Betrò, 1995. Hieroglyphics: The Writings of Ancient Egypt, “City Plan”, p. 190.

2. ^ Budge, 1978, (1920) An Egyptian Hieroglyphic Dictionary, “fortress”, (no. 35, 36, 37),

3. Betrò, 1995. Hieroglyphics: The Writings of Ancient Egypt, Betrò, Maria Carmela, c. 1995, 1996-(English), Abbeville Press Publishers, New York, London, Paris (hardcover, ISBN 0-7892-0232-8)

4. Budge. An Egyptian Hieroglyphic Dictionary, E.A.Wallace Budge, (Dover Publications), c 1978, (c 1920), Dover edition, 1978. (In two volumes, 1314 pages.) (softcover, ISBN 0-486-23615-3)

Schulz, Seidel, 1998. Egypt: The World of the Pharaohs, Editors, Regine Schulz, Matthias Seidel, Könemann Verlagsgesellschaft mbH, Cologne, English translation version, 538 pages. (hardcover, ISBN 3-89508-913-3

I would also urge everyone to read these books prepared by UNESCO from The Cairo Conference held in Cairo, Egypt from January 28, 1974-February 3, 1974.

(1) ”General History of Africa: Ancient Civilizations of Africa”, volume #2″, prepared UNESCO, Editor GMokhtar

(2) “The Peopling of Ancient Egypt and the Deciphering of the Meroitic Script”, by Cheikh Anta Diop, Jean Leclant, Theophile Obenga, and Jean Vercoutter

(3) “African Philosophy: The Pharaonic Period 2780-330 B.C” by Dr. Theophile Obenga

Now, to those who disagree with all of the documented evidence, including Linguistic evidence that I’ve presented here, write a Linguistic thesis and present that Linguistic thesis to a Linguistic Journal of your choosing for ‘Peer-Review’ or be quiet until you do.

Let’s see whether or not your assertions are correct. Because, as of today, my stance has been academically accepted and has been ‘Peer-Reviewed’.

Like Our Story ? Donate to Support Us, Click Here

You want to share a story with us? Do you want to advertise with us? Do you need publicity/live coverage for product, service, or event? Contact us on WhatsApp +16477721660 or email Adebaconnector@gmail.com